In early 2020, as reports of a novel coronavirus spread, the eerie headlines and growing sense of collective unease began to feel strangely familiar to our team at Flying Object, thanks to Spanish Flu Now, a project we created two years ago.

Spanish Influenza struck in 1918, at the tail end of WW1, devastating the global community. Most estimates believe there were up to 50 million deaths, but some speculate it could have been as high as 100 million. Unlike most influenza outbreaks, which are usually high risk for the very old or very young (as well as those with other health issues), the Spanish flu was also particularly fatal to those between 18–34 - the same age as today’s “millennials”.

With many young lives already lost to conflict, the pandemic represented an immense tragedy. Despite this, it faded quickly from public consciousness. Coming shortly after the Great War, and with World War II following a couple of decades later, perhaps it was overshadowed in many peoples’ minds.

In 2018, dance studio Shobana Jeyasingh Dance embarked on a project remembering the Spanish Flu a century on: a piece called Contagion that explored the experiences of people affected by it and its impact on society. We were invited to work alongside them, on a digital art project that reimagined the flu as if it were happening in the present day, as seen through Instagram.

Fast forward a couple of years to the outbreak of coronavirus, and the parallels between the project we had created and the real life tragedy unfolding before our eyes were stark. It goes without saying that reflecting on Spanish Flu Now in light of recent events was disconcerting. But it also stirred some thoughts as to the function of projects like these in our society - one which has allowed Covid-19 to decimate its arts and culture industry this year.

With Spanish Flu Now, we wanted to use social media to explore how a global pandemic would be reflected in today’s fast-moving world of youth and web culture. We used Instagram to tell the stories of six fictional characters caught up in the pandemic, the events of Spanish Flu playing out in real time on their feeds through the lens of their own unique perspectives.

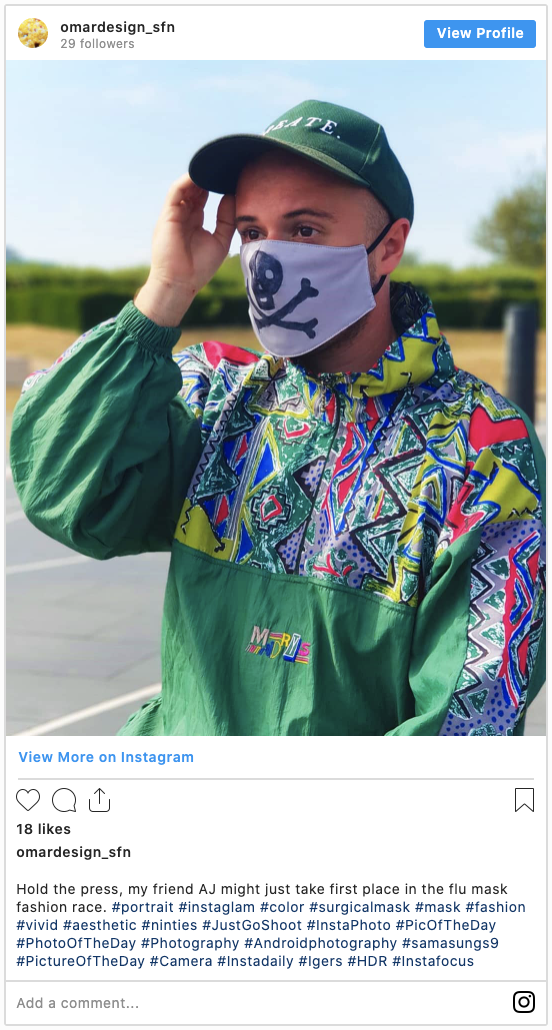

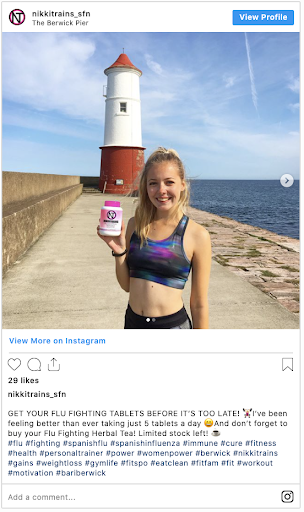

We worked with five writers, photographers and artists from around the UK to create Instagram accounts for the digital avatars of our characters, such as Nikki, a personal trainer, Kirsty, a trainee lawyer and Santh, a pregnant woman. As the situation developed, we saw them suffering, helping others, trying to escape, or simply attempting to understand the world-changing events they were living through.

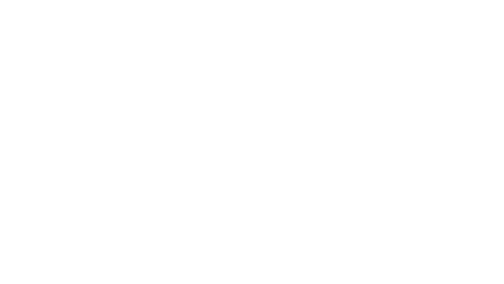

Masking up

Looking back at the project, some of our assumptions about the impact of digital communication and internet culture during the spread of an infectious disease proved fairly accurate. Selfies taken in masks have been widespread on social media, with brands providing trendy options for the fashion forward and influencers pairing every outfit with a different design.

Personal storytelling through social media

As in our fictionalised stories, social media posts have told the human story of the pandemic, with personal expressions of grief on Instagram and Twitter forming a collage of collective loss in the digital spaces we frequent.

Discrimination and bias

Our character Rosa - originally from Spain, now working as a cook in a care home - experiences discrimination and social isolation as a result of speculation about the flu’s Spanish origins. Sadly, elements of her fictional narrative were mirrored by the anti-Chinese sentiment that was found during the early months of coronavirus.

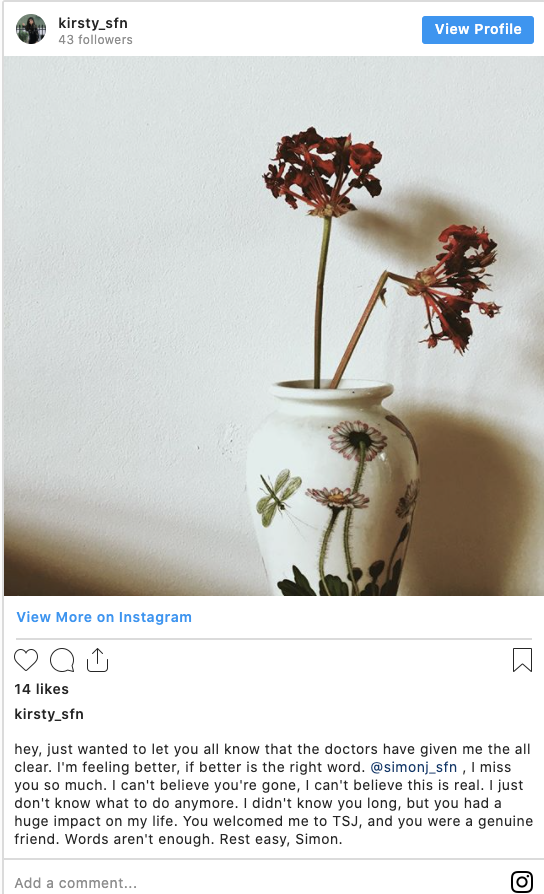

Local heroes

In a more positive instance of life imitating art, the respect and admiration shown for essential service workers became a central narrative that emerged in 2020. This was a phenomenon our stories had also explored, seen through the character Nathan, determinedly delivering meals to vulnerable people in his community.

The pitfalls and promise of social media

Based on reports of quack doctors peddling dubious cures during the 1918 Spanish Flu, we had imagined social and traditional media becoming platforms for an exploitative industry of ineffective remedies and misinformation (some almost as wild as Donald Trump’s bleach comment this year).

But while it’s true that anti-maskers and covid-deniers have made use of social media to further their agenda, many in our society have harnessed its power to disseminate crucial resources and connect people. In crafting our stories we perhaps didn’t fully consider the benefits felt when people pull together and use the opportunities of our digital world to make a positive difference at a time when many were physically isolated.

Mass communication for public health awareness

From the initially successful “Stay Home > Protect the NHS > Save Lives” campaign, to the less convincing “Hands. Face. Space” relaunch, the way the government has communicated to citizens this year has been an on-going talking point.

In Spanish Flu Now, our character Omar, a young artist and designer in Manchester, shared public information campaigns and other advertising he spotted. Comparing these imagined pieces with the real thing two years later, it’s fascinating to notice similarities in design and tone - a combination of a public health aesthetic, with warning graphics straight out of a dystopian sci fi movie.

Art as a means to reflect

In 2020, with the arts sector on its knees and freelancers struggling without sufficient governmental support, one detail of Omar’s story in particular stood out to us: his ability to continue working throughout the pandemic. This year many real-life Omar’s have fared extremely poorly by comparison.

Looking back on the project has reinforced our belief that the arts play a vital role in a reflective and conscientious society. The creatives we worked with in Spanish Flu Now aimed to commemorate an event from our collective past, and interpret it on an individual, human scale, to help audiences connect emotionally. It is a goal shared by the original Contagion dance piece, and hundreds of other commissions in the 14-18 Now centenary.

We’re currently working on a new project with Wellcome in response to the Covid-19 lockdowns. Covid Living, launching later this year, is focused on learning from and providing resources to young people processing isolation. In making it, we’ve collaborated with all sorts of talented creatives, from poets to illustrators to sound artists. Developing it with Wellcome has felt like an affirmation of values that are really important to us as a company, and hopefully to the wider industry.

Artists and creatives are uniquely placed to help us work through collective trauma and find meaning in difficult times. A priority for our leaders today should be protecting the arts and creative industries, to ensure when the crisis finally ends, we are left with a functioning sector, able to play it’s role in helping us remember, understand and process the experience we have been through.