I’m addicted to Wikipedia. That’s probably a good starting point for explaining how I became an Art Director. Which is to say, I’ve never really been the sort of artist that honed one skill set, or one particular field. Frequently, especially when I began my Master’s degree at the Royal College of Art, I was very self-conscious that my knowledge and interests were vastly horizontal. I went into that degree with the idea that I needed to find a focal point, something a bit more viable and useful.

Instead I just got more and more excited about incongruent subjects. There’s no clear relationship between a series of comics drawn with my wrong hand and table football, for example, or quantum physics and Jeanette Winterson, all of which I delved into at RCA. Essentially, I did the opposite of what I’d intended: the line of interest just got even more horizontal than when I started.

It was a similar story when I was studying at Glasgow School of Art after leaving school. I was encouraged to take architecture because it was a bit more academic. It was a bit more purposeful than what I’d been doing at school. There, I’d been lucky to have a great teacher who, aside from explaining how to get 100% at GCSE, which was quite appealing, drilled into me that art wasn’t just about being good at drawing. Instead it was about reinterpreting work, getting excited about it and playing around with things. Which I was pretty good at. I spent so much time in the art department that I accidentally ended up calling that teacher dad multiple times.

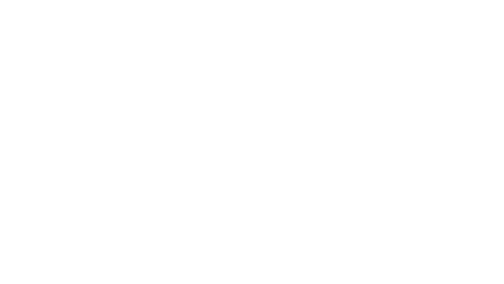

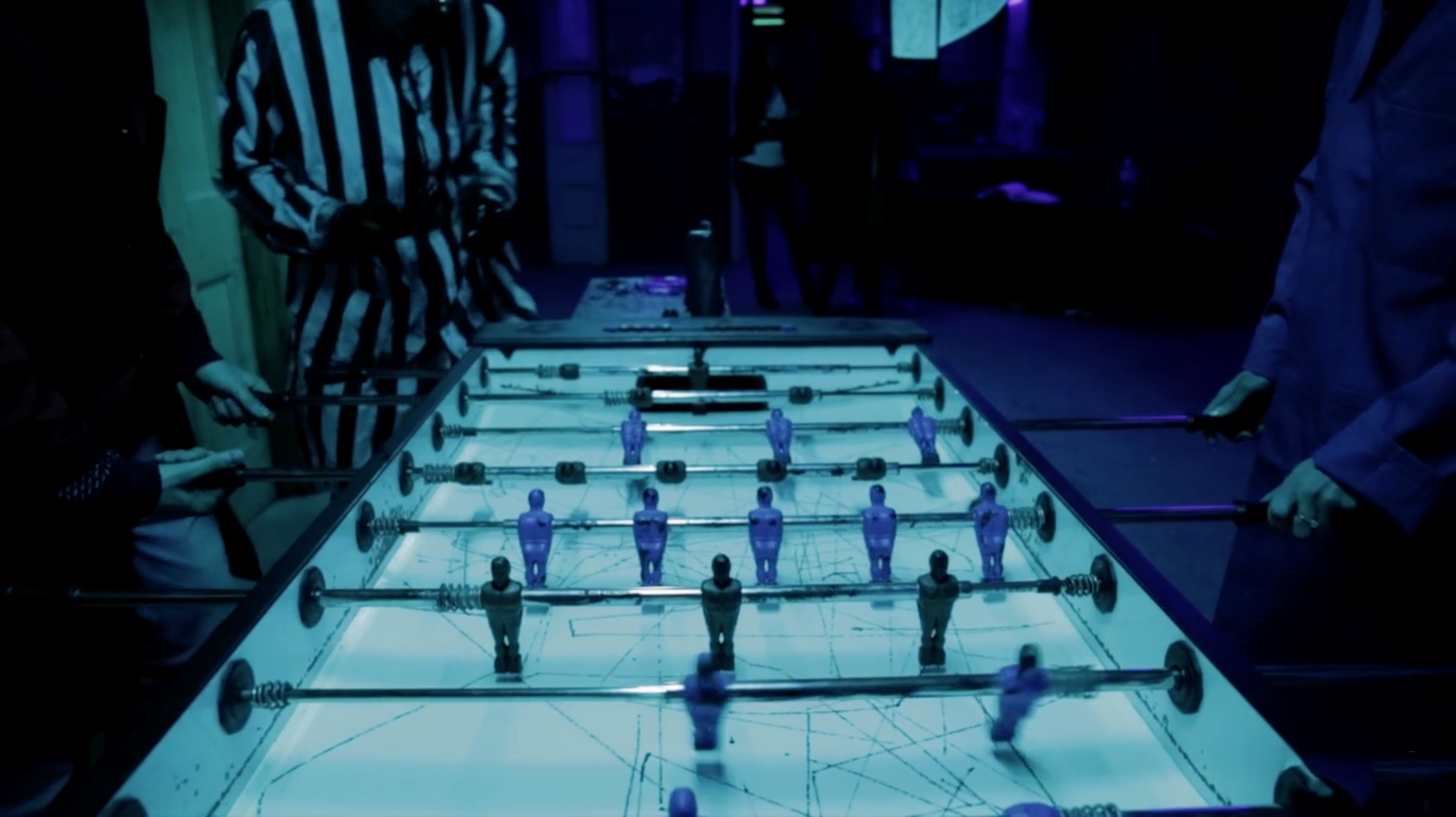

One thing I got really excited about was the CoBrA, a group from the 1940s and 1950s from Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam, and their vibrant, sloppy, messy paintings. I read about one of the group who became a situationist and invented a game called three-sided football, which was basically a line drawing of a hexagonal pitch with three goals and three teams. I remember thinking, holy sh*t, this is just a drawing and a set of tiny instructions, but it’s genius – this really pure idea.

The first and only recorded game of it at the time was in the 1990s in Glasgow. So, I decided to organise a game of it. It ended up being a lot of fun, and one of many things that made me love art school – another was the breakcore night I ended up running with some friends. Admittedly, I should have probably been more focussed on studying, but to be honest I wasn’t all that good at Architecture. I chose it because it was a job I’d actually heard of – a job you see people doing in rom-coms or on the telly. I didn’t really know what a graphic designer was when I was 18 and I’d definitely never heard of a creative agency.

I’ve spent a lot of time in between studying or working doing odd-jobs. When I left Glasgow and moved to Athens for a while, I ran art workshops for a DIY project based on the idea of learning through play. I was basically living on about two Euros a day, finding my way a bit. I spent a bit of time working in a call centre doing government surveys (a strange job calling randomly selected, often bewildered businesses) when I moved back to the UK. It was so awful that at one point I had a slight mental breakdown and walked out into York for about three hours, crying. Then I went back and realised that no one had realised I left – that just about sums it up.

The toil was to pay for a short move to China, where the odd jobs got significantly more odd. I did things like get paid to go laser questing, or sit in on business meetings so that companies could appear as though they’d employed European people. I also had my first and only foray into modelling where my only instructions were to “look like a sad prince”. And no you definitely can’t see those photos!

I had a lot of time to think in China and started building a portfolio so, after completing another short NQ in screen printing back in Glasgow, I applied for a Master’s degree in visual communication at the Royal College of Art. I threw myself at every project I could manage there and especially loved that there were live briefs with organisations like The Science Museum and the Institute of Physics. Probably my smartest career move was working at the bar. It meant I met people from more or less every single course, which was incredibly valuable. Every shift I had I’d be chatting to someone from vehicle design, or someone working in fashion, or painting or sculpture, or something I’d never even heard of, about what they were doing and what they were interested in. I just learned so much, from many different perspectives. A lot of the people I met at RCA are still my closest friends and some have become a sort-of freelance family; many collaborate with Flying Object now.

While there was another short period of – you guessed it – odd jobs, for example painting a collapsing house in Notting Hill for an artist doing a Frieze dinner that the Prince of Sweden attended, in less than a year I was working with Flying Object. My first project was with Intel and the Royal Shakespeare Company, who were putting on a performance of The Tempest which involved a bunch of live motion tracking – a real technical spectacle at the time. We came up with the idea that we’d conduct a giant projected digital storm using a consumer grade Intel camera that recognised gloves or a couple of batons, making lighting come down from the sky, or crashing thunder. In the exhibition space we also reimagined Prospero’s cell as though Miranda had grown up there but in modern day. Because in the plot they’d been stuck on the island for 12 years we filled it with 90s and Y2K stuff, like a poster of Leonardo DiCaprio in Romeo and Juliet, next to a classic AC Milan strip.

I’ve worked on so many brilliantly weird projects with the company since then. One of my favourites has to be Scottish Twitter. Having lived in Glasgow for around 5 years or so on and off, I really understood the community and had such a varied role – coming up with ideas, curating, doing stuff that felt really original. Maybe it didn’t look as slick as Dating Twitter, which I also loved, but sitting in that space when it opened and watching everyone who went there laughing their asses off was so rewarding. It’s because we made something that people really saw themselves in and was properly integrated into a community.

Despite my best intentions, I never really nailed narrowing my interests down to one specialty. I have every other Friday off as a studio day to work on my own projects (and continue my obsession with Wikipedia). I’ve always been fascinated by linguistics and, in 2022, I discovered a Cypriot writing system from the Iron Age. It was a syllabic system rather than an alphabet; it looked alien, like something from a sci-fi film, and only died out in the fourth century BC – it ran concurrently with the Greek alphabet for a good while. I had an idea for a project imagining that it never died out. What would a street sign look like? Or a takeaway menu?

I needed to learn more about the writing system and how it worked, so I contacted an academic at the University of Cambridge, Dr Philippa Steele, who told me about a fellowship programme they run. Flying Object allowed me to take three months out. I spent that time talking to people much smarter than me and trying to create fonts and signage out of a writing system that hadn’t been used for over 2000 years. One of my favourite things I did there was to make a Comic Sans version of the syllabary.

Is it viable and useful, like those intentions I started out with years ago? Probably not. But now I know that’s a good thing: the point is being interested. I’m still working on expanding that broad horizon. Or, to put it another way, I’m still spending a lot of well-spent time on Wikipedia.