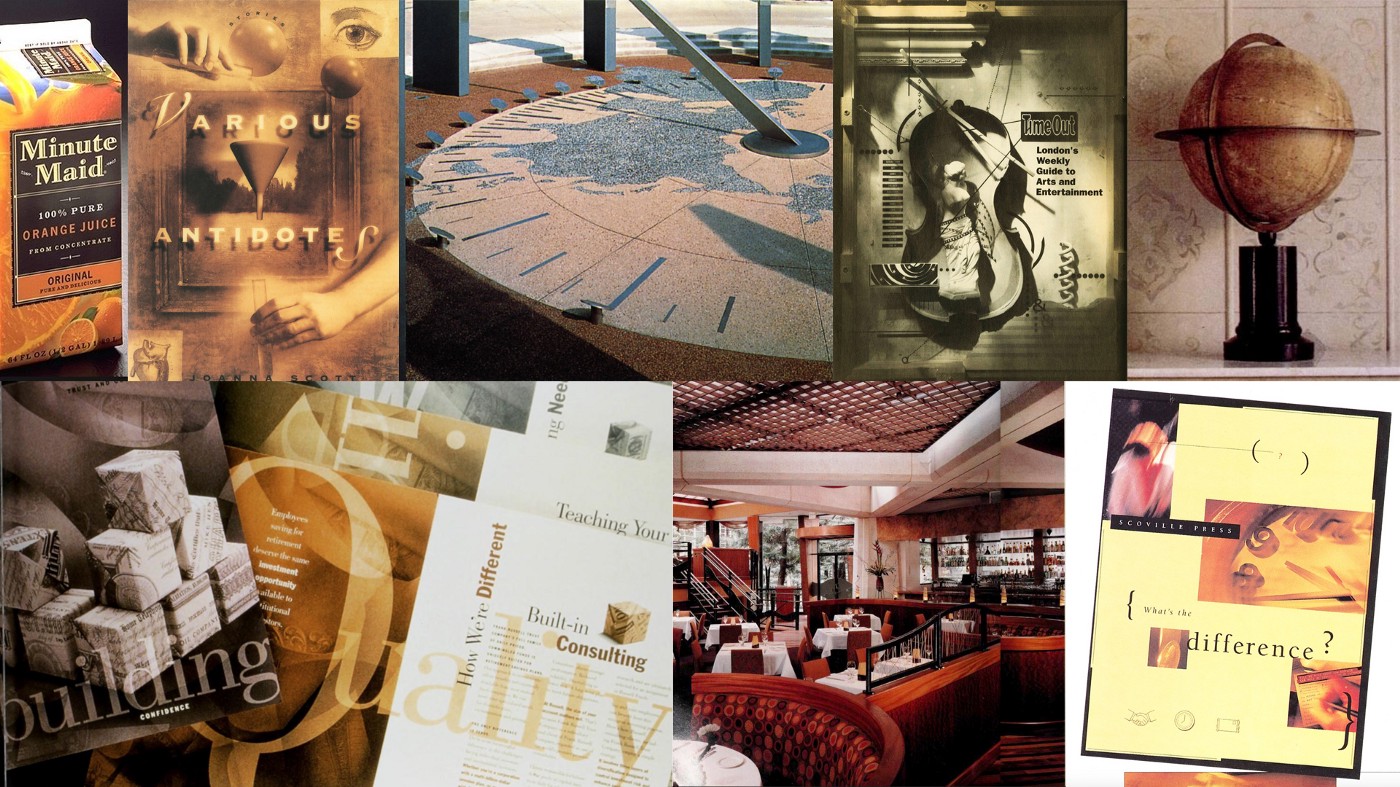

This is what I thought when a friend invited me to join Global Village Coffeehouse, a Facebook group dedicated to a specific 90s aesthetic trope. It was instantly familiar, yet something I hadn’t seen in well over a decade. A sort of faux-naive, wood-cut, pseudo-tribal look populated by jazzy symbols of dancing people, suns and aroma swirls. It started to trigger weird distant memories in my brain — scrolling through clip-art libraries the first time my dad took me to an internet cafe; the washed-out, world music, wholegrain, groovy shirts my art teacher used to wear. As obscure as it sounds, you know this style.

Inside the group, a lively community discusses and dissects the crowd-sourced images, identifying canonical motifs and defining the boundaries of the aesthetic. Posts of ancient website screenshots, café menus, product shots and sightings of rare survivors out in the wild are met with enthusiastic analysis and taxonomy.

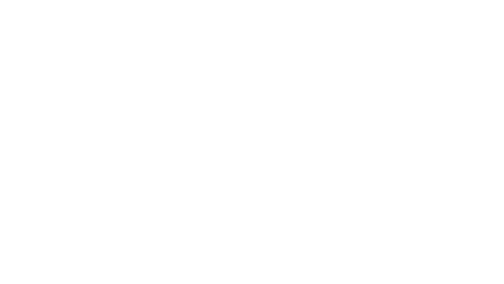

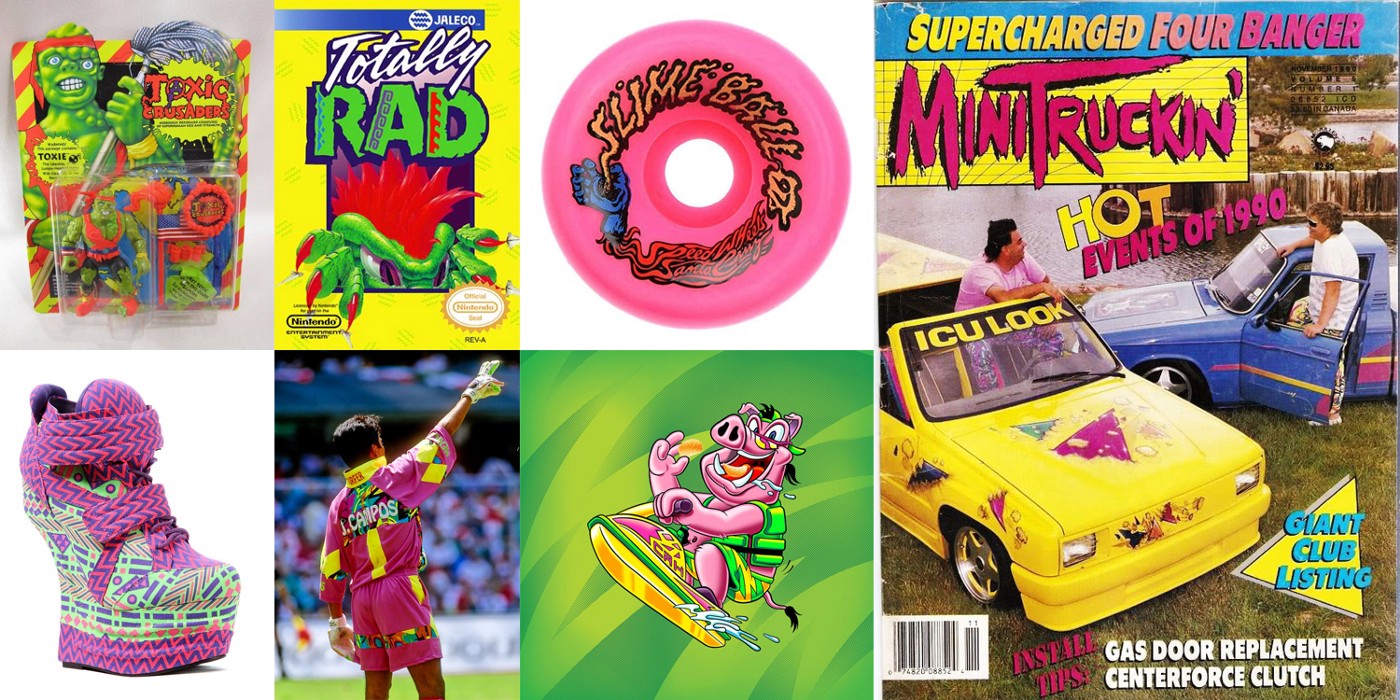

Soon my sidebar was filling up with recommendations for groups with names like Factory Pomo, McBling, 90s Urbane (Frasurbane), Neon Ooze Surf Shack and four colours. They all follow the same directive: identify a design style from recent history; give it a suitable name; and then start sourcing, discussing and categorising examples. The crowd-sourced format, combined with the desperate desire for peer recognition that social media induces, allows a rigorous, networked design-research machine to be enacted.

When successful, the result can be extremely exciting and satisfying. Suddenly a group of intangible visual unifiers have a name: you can talk about them, reflect on them. You can place them on a timeline and see these movements peak, blend, fragment and fizzle out.

It seems that the administrators of these groups are part of a small, tight-knit community of researchers dedicated to the rediscovery and taxonomy of recent design aesthetics in modern consumer culture. One key player is Evan Collins, a young architect based in Seattle, who has set up CARI (The Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute), an umbrella exploring multiple separate aesthetic channels. You can read an interview Evan did with the Guardian back in 2016 on Y2K aesthetics and what this kind of research can tell us about the world at a given time and context, or an excellent short essay on Global Village Coffeehouse Aesthetic.

It made me wonder: what visual tropes are dominating the consumer design landscape now? Are there tropes I am too immersed in to properly perceive? Some time, in the not-too-distant future, will they look as esoteric and dated as Global Village Coffeehouse? Am I unwittingly contributing to one such trope that will, in a few years time, be a screenshot on a forum, unearthed by a digital archaeologist and categorised accordingly?

My overwhelming feeling after diving between these groups is optimism; that there is at least one wholly positive culture that is developing from social media — a communal effort to document and discuss the aesthetic worlds of our recent past, hidden away in private groups. This kind of activity feels like an echo of the optimism surrounding the early age of the internet, before we became so jaded and distrustful, back when the internet was full of little pseudo-tribal figures surrounded by woodcut swirls and jazzy zig-zags.